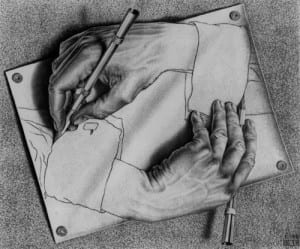

There’s a new thread running through my PhD reading and reflection; how little has changed with ‘e-learning’. In the digital education world, innovators and technologists have raced ahead – buoyed with project funding – reinventing multiple wheels and embracing the new affordances of social media, demonstrating their connectivism from tweeting cliques – while many more staff remain excluded from the mysteries of social media and virtuality, following the traditional lecture/seminar models and wishing learning technology would quietly leave the building. I find myself somewhere between the two. I’ve been reading Feenburg (see the PhD page) In the ninth of his ten paradoxes of technology, the co-construction of technology and society and resulting feedback loops are demonstrated through Esher’s print ‘Drawing Hands’. Like a Mobious Strip, or the chicken and the egg question, the print confuses our expectations of order. It reminds me of the VLE – the only way to learn it is to use it but how can we use it without supporting the learning?

When VLE’s were first embedded into university systems there were expectations of adoption and use e.g.HEFEC’s Technology Enhanced Learning Strategy full of the rhetoric of transformation. Over on the Phd page I’ve quoted Feenburg who said in 2011 ‘the promise of virtual learning in the 1990s has come to nothing and elearning within the university has failed’. I’d suggest it hasn’t failed; more not worked out as well as it could have done. I’m a learning technologist with a remit to support virtual pedagogy. Failure is not an option. I still believe in the affordances of technology – access beyond the barriers of time and distance – and the potential power of online communication and collaboration to create communities of shared practice where learning takes off and runs. The best way forward is working directly with teachers and learning developers on how best to enable their own digital scholarship and literacies. There’s no secret to effective online learning. We know what works. Give staff time, space and incentivisation to adopt digital ways of working alongside a reliable knowledgeable support system – and they will – the TELEDA course shows enthusiasm and interest is there. What’s missing is the time, space and incentivisation – and a support system robust enough to reach across the schools and departments. The reason the OU do it so well is the resource they put into it. The reasons other institutions do it less well is their DIY approach to technology; elearning hasn’t failed, it just needs a different strategic approach to innovation.

Reading the literature around technology and society is to visit some gloomy, pessimistic viewpoints. I agree technology is devisive. Access to technological resources can be seen to replicate wider social structures of disadvantage and marginalisation. But I need to be optimistic. I don’t see technology for education as necessarily essentialist – or as Douglas Kellner says in his response to Feenburg’s book Questioning Technology –‘…having a primary dimension which is functional…instrumental, decontextualizing, reductive, autonomising and determinist.’ P161-2. Those who interpret it this way miss the creative potential of the user. I remain positive. Given the time, space and incentivisation to integrate and contextualise the use of technology, it can be enriching rather than dominating and reductive.

This is my motivation for adopting an action research methodology for my research one which invites staff to participate in a process which seeks to improve relationships with an institutional VLE. I believe without investment into the staff who use it, who are best placed to say how they could use it more effectively, there can be no freedom from the loop of resistance. Without participatory research into the staff experience, resistance to the VLE will continue, it will be negatively critiqued, and used on a ‘needs-must-if-at-all’ basis. I do believe VLEs can be used effectively to enhance teaching and learning for on campus students and provide a valid alternative for those learning in isolation at a distance. I also believe staff are excited by the potential of new digital media but lack the opportunities to develop the new ways of thinking and managing their practice. The pilot run of Teaching and Learning in a Digital Age is already suggesting this. The challenge now is to investigate how best to manage this process before the next academic year.

Feenberg, A. (2010). Ten paradoxes of technology. Techné, 14(1): 3-15.

Feenburg, A. (2011) Agency and Citizenship in a Technological Society http://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/copen5-1.pdf

Kellner, D. (2001) Feenberg’s Questioning Technology in Theory, Culture & Society, Vol. 18(1): 155-162, 2001.