The current iteration of TELEDA is over. I shall miss it. Nothing is as effective as applying theory to practice and when it comes to e-learning – there is a lot of theory out there. I learn more about the challenges of teaching and learning in a digital age every time and I hope colleagues do too. Feedback suggests it’s a useful experience but what can’t be predicted are the outcomes. This is what I’ve started to call the Pedagogy of Uncertainty. When you begin to teach and learn online, you are up close and personal to the unknown and very soon get to understand there is nothing cost cutting or time saving about digital education. Retention within virtual courses is traditionally poor. It’s easy to see why. Without the physical timetable of lecture, seminar and workshop events, online learning is invisible. Easy to ignore. Without the face to face stimulus of personal communication, you are dependent on text. One of the first lessons is how easy misunderstanding occurs when the only language is letters. Not everyone is comfortable with writing rather than speaking.

The current iteration of TELEDA is over. I shall miss it. Nothing is as effective as applying theory to practice and when it comes to e-learning – there is a lot of theory out there. I learn more about the challenges of teaching and learning in a digital age every time and I hope colleagues do too. Feedback suggests it’s a useful experience but what can’t be predicted are the outcomes. This is what I’ve started to call the Pedagogy of Uncertainty. When you begin to teach and learn online, you are up close and personal to the unknown and very soon get to understand there is nothing cost cutting or time saving about digital education. Retention within virtual courses is traditionally poor. It’s easy to see why. Without the physical timetable of lecture, seminar and workshop events, online learning is invisible. Easy to ignore. Without the face to face stimulus of personal communication, you are dependent on text. One of the first lessons is how easy misunderstanding occurs when the only language is letters. Not everyone is comfortable with writing rather than speaking.

Online its more difficult to get to know people. Over time, virtual colleagues develop a unique voice and personality but it takes a while for online community to develop. The risk is people leave before this tipping point occurs. It isn’t easy to teach or learn online which reinforces recent calls to recognise elearning has failed. The early promises of transformation were never based on real world experiences. Rather they evolved from the techie experts or those who mandated use without getting their hands digitally dirty. What’s always been missing is the lived experience of staff who teach and students who learn in physical classrooms. When they find themselves on a virtual brick road instead, it’s where the problems begin. The theory was never written with them – only for them by others.

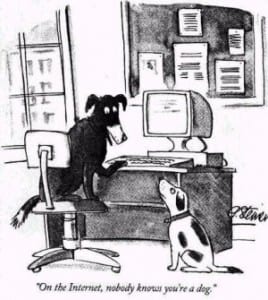

Face to face offers clues to identity but online we are reduced to text. Now TELEDA has a sister. TELEDA1* and TELEDA2** both have learning blocks which focus on communication and collaboration. TELEDA1 is text based. TELEDA2 will use video like Skype, Google Hangouts and Blackboard Collaborate. I want to keep it this way. Part of the TELEDA1 process is to encourage colleagues to reflect on the limitations and advantages of text. It’s about stripping communication down to the essentials. I suppose it’s a bit indulgent on my part because I’m intrigued with subjectivity – postmodern style – in particular how we see and present ourselves online.

Postmodernism has always been contentious and it’s brief period in the spotlight was prior to the rise of social media. elearning might not have lived up to it’s early hype but if anything has had its transformation promise realised, it’s social media. Instant, continuous connection across all boundaries of time and distance. Is there were a way to combine the two – or are the words social and educational always oxymoronic.

Postmodern theory suggests we are the products of ideology; located within discursive power structures, giving away our social position through language, replicating and reinforcing our own oppression. I’m not a Marxist. There are more forms of oppression than one.

The body is a powerful delineator of social position. Cultural attitudes towards gender, ethnicity and disability produce marginalisation and dis-empowerment which cut across class difference and economics. But online no one knows who you are. Without visual clues, the identity game is played differently. This is a layer of TELEDA which offers the potential for equality. By keeping the video out of it, I hope it also offers a valuable transferable experience.

—————————————————————————–

* TELEDA 1 – Teaching and learning in a digital age; design and delivery

**TELEDA 2 Teaching and learning in a digital age; eresources and social media

——————————————————————————————————————————